Becoming a Great Musician

This interview was originally published in September 2012.

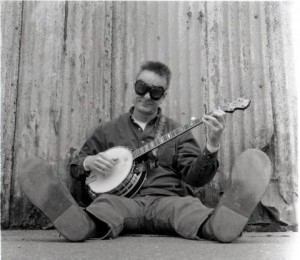

Danny Barnes is a banjo player and a songwriter who has been a working musician for over 30 years. Widely known as one of the world’s most innovative and versatile artists, he mixes non-traditional music like rock fusion and jazz with electronic percussion instruments, still rooted in the traditional bluegrass, country and folk music for which his instrument is known. A lifelong music “fanatic” in every sense of the word, he decided he would make a career in music at 10, when, deeply inspired by the many records his parents played at home, he began to diligently study his craft. Known for his positive and refreshingly-honest attitude towards being an artist in the modern music industry, he continues to dedicate himself to growth and further innovating his instrument by learning from and collaborating world-renowned master musicians, including Bela Fleck, Lyle Lovett, Nickel Creek, John Popper, Chuck Leavell and Dave Matthews. He puts out music through ATO Records.

I had the pleasure of talking to Danny about his long career in the music business and his views on the modern music climate. He also shared some advice for artists that want to successfully build their lives around music and become truly great at their craft.

Musician Coaching:

Thanks for taking some time to chat, Danny. How did you get started in the music business?

DB:

When I was about 10 or 11, it just became clear to me that music was what I wanted to do. I’ve been pretty focused on it ever since then, and I just turned 50. I’m still working on it, still taking lessons, researching and developing as an artist. But it all got started officially when I was a little kid.

My parents were music fans and played a lot of records around the house. And my brothers were really into music, too. Somehow I got it into my head that music was what was most important. And that’s what I’ve continued to believe for about 40 years.

Musician Coaching:

Was there a particular point where you discovered you would be able to do it for a living vs. just as a hobby?

DB:

I think I pretty much knew it from the beginning. It was just a matter of figuring out how to do it. At first, it was definitely just that dream of wanting to be a musician. But I was wired to be a real music person. I really enjoyed records and going to shows, so one of the things that has always driven my attention and interest in music is wanting to make things that I would like to hear. I’ve been doing that since I was a kid, and that’s still the force that drives me: I like records and buy records, and want to make things that would interest me as a music fan. I haven’t put the focus on the economic part of it. I’ve been spending most of my time learning how to be great, which involves studying the work of the masters.

I grew up in a really small town. And in this small town, there was a guy who fixed hot rods. He had a little garage and would just work on hot rods to get really good at it. He decided that was what he wanted to do and just adjusted his life so he could do it. Guys like that became role models for me. They could be motorcycle racers, bass fisherman or guys who fixed hot rods. But they were all guys who were into something and figured out a way to do it at any cost.

What I think is fundamentally important for me and my own expression is just being a music fan and starting from that premise. I am just really driven by music and believe in the power of music and continue to be curious to learn about all its aspects.

Musician Coaching:

Well and “fan” is derived from “fanatic,” so I think you’re on the right track there.

It’s interesting that you describe deciding to do music full time as an evolutionary process. I think a lot of people have this idea that you just up and decide to be a musician, then stop everything, quit your day job and spend a lot of time, energy and money on becoming a musician. I’m always trying to preach to people that it’s about baby steps – slowing migrating the different areas of your life towards music.

You’re a guy who has been playing music for a living for decades. What do you think you’ve done right that has allowed you to make a career out of playing music?

DB:

I made a lot of mistakes, because I didn’t know about things like contract law and how other people in the industry think. And I continue to make mistakes.

What keeps me going is, I pretty much knew what I wanted to do when I was a kid. I’ve gone through small periods of time when I’ve questioned what I’m doing, when I’ve thought about doing something like computer programming, being a merchant marine or starting a small business. But basically, I’ve known for a long time what I wanted to do. I think having that conviction solves a lot of problems. The French have that term “raison d’etre:” “reason to be.” I think if you know what that “raison d’etre” is for you, everything becomes a lot easier. If something crops up, you can ask yourself if it is contributing to you career and helping you get stronger, or if it’s dragging you down.

Living a really simple lifestyle and not being in a lot of debt has also been really good. When I was in college, I was really broke. And I learned how to do things without spending a lot of money and being able to entertain myself and find happiness without a lot of dough. Because I had that skill, when things got rough,something didn’t come through or I’ve had to take some time to learn something in order to go on, I wasn’t stressed out of my brain trying work three or four different jobs to get me through, then feeling resentful towards my passion for music for not providing me with the opportunity to make money. I can’t necessarily recommend keeping your life simple, even though that’s what has worked for me, because a lot of people aren’t really interested in that as an answer; it involves giving things up.

As an example, my pickup truck is worth about 300 dollars. But I have some really nice instruments. I’m more interested in buying the nice preamp I want than I am in buying a nice car. And I travel a lot in my work, so I’m not really interested in going to the Bahamas on a vacation. I just really want to work. Not getting worked up about money has allowed me to stay creative, because I don’t have a lot of economic baggage. I’m not even aware of this in my own life, but I do see other people struggle as they move through their story arc. Sometimes they seem to get bogged down in money, and it diverts attention from creating art.

So, there are really two things that have helped me continue to stick around and play music: being really clear about what I wanted to do; not being in a lot of debt.

Musician Coaching:

You’re a guy who has put out records through ATO, and of course, you’ve worked closely with a lot of great artists like Dave Matthews. How did you fall in with musicians of this caliber?

DB:

I just practiced my ass off. I’ve worked so hard. My thinking was that you have to strive to be absolutely great at something. I think a lot of times, it’s possible to get fixated on getting your promo shots together, putting together a website, getting all your materials together on going through the motions of the mechanics of creating the illusion that you’re making music. But then when you sit down to play, there isn’t anything that good coming out. Granted, there are a lot of people on TV that do that and are huge celebrities. But there isn’t that much happening with their music. That confuses people.

Musician Coaching:

Well, and I want to ask you about that. You strike me as a very grounded man, which leads me to believe that mass media does not have a big effect on your life. What I’ve found as I get older and work with younger people is that when people are coming up with goals and asking me what I can do for them, they will think something along the lines of, “How can you make me the next Justin Bieber?” And TMZ or VH1’s Behind the Music devote three minutes to the struggle of becoming a musician and 20 minutes or the rest of the hour to the problems of fame. Do you think the slanted view mass media presents of what it means to be a musician is a problem?

DB:

Yes. I think so. It’s kind of like camping: There are people who live in the woods and people who camp. Camping is cool, but if you are trying to live in the woods and there are campers basically coming into your yard, it’s kind of a hassle.

What I figured out when I was a little kid in the early ‘70s and late ‘60s was the concept of greatness. I realized that the goal is to try to be great at something, whether that be mixing, playing the trombone, writing songs or anything. You need to be great at it. I don’t think I’m there yet. I’m still working on it and trying to get there.

It’s possible to mimic things closely. We can find someone down at the bus stop, get them a makeover, auto-tune them and make them look and sound a lot like a guy on TV. I think that’s distracting. The response that creative people should have to stimuli is to make something. Imitating somebody is not making something. I’m not saying you shouldn’t gather inspiration from people. But our response to being inspired should be to create something ourselves.

It’s so easy to get confused and distracted by the mechanizations of this mass group of people – musicians – and get lost in what they’re doing.

Musician Coaching:

I am inspired by the fact that you’ve made a pretty amazing name for yourself and are also putting out the kind of records you want.

I know you’ve been really focused on becoming a great player. But what role has networking played in your career?

DB:

I’m just horrible at networking, to be honest. I’ve never been able to make it work. That’s just not in my repertoire. And I don’t respond to it very well either. I have my friends that are my friends. And some of my friends are very powerful guys in the music business. And some are janitors at nightclubs or bus drivers.

My fans reflect that, too. I’m pretty esoteric. You have to already know about my music to be aware of it. My fans know about a lot of different kinds of music and are part of a small group of people that tend to be pretty diverse, interested and interesting. I look at my fans as just more people I know and an extension of my friends.

I think people put too much emphasis on networking. And people who are really successful at networking can be confusing to other musicians. They might think, “Here’s a guy that had a million downloads and has a ton of followers on Twitter.” And while it’s true that anything can happen to anybody, a different person might not get the same results.

Musician Coaching:

I really appreciate you being honest and really speaking from your experience. What advice would you have given yourself when you were just starting out?

DB:

I would say, “Keep practicing; keep working.” Because, working on your craft is the thing that’s so easy to get distracted from doing. But if you keep working, developing, growing, learning, researching, editing, writing and making, you will become a real musician. The way I look at it, making $1 million off singing someone else’s song doesn’t make me a musician. What makes me a musician is continuing to grow and to have a creative response to things, coming up with new contexts and configurations and structures. That’s definitely what I’ve done from the beginning. I don’t even know why I knew to do that. It’s just what I was interested in. I was always interested in learning, so I learned. I was interested in developing combinations of sounds that were not on other people’s records, because it interested me. In a way, it’s the same theory behind Immanuel Kant’s philosophy: How could the universe be any other way than the way that it is now? It has to be this way. There was just no other way for it to be for me.

I would also tell myself to hang in there and keep at it, even when I come across distractions. It’s easy for someone to say, “If only I get this boob job, I will get noticed and it will help my career,” or “I need to move to this city,” or “I really need to get my EPK together.” And in the meantime, that person can’t even read music. And it’s not that reading music is always necessary, but it’s easy to get distracted from actually getting better at playing music with all that’s going on out there.

I’ve always considered myself to be the postman and not the mail. I’m just freaked out about music, because it is so amazing. I’m not saying, “Look at me!” I’m saying, “Hey! Music is really awesome. Look at all the things you can do with it! I’m going to try to do something different here.” And I may fall on my ass. In fact, I probably will. But at least I am trying to make something that’s my own and trying to give something back.

I’m also not a good imitator. I’ve tried to play like other people, but I’m just not very good at it. I am good at thinking up ideas, though and at coming up with songs, developing a concept. I can put an idea together, do a four-album story arc and put it all together with motifs that relate across the narrative.

Another thing I’ve realized is, for me music is how I learn about the world. I put together these records and work on them really hard, and then I get to learn things through that process. For example, music is why I’m talking to you and getting to know you. Without it, I wouldn’t be having this experience. And when I go on the road, I may get on an airplane and fly to LaGuardia, then rent a car or get on the subway and head down the Village to play a show. I wouldn’t have done any of that if not for music. Music is why I get to do everything I do and how I experience my entire life. It’s the way I relate to the world.

Musician Coaching:

You’re obviously a big proponent of shedding – practice, practice, practice. What about learning through collaboration?

DB:

Absolutely. I’ve learned so much from not being afraid to be the worst guy in the band, finding masters close to where I live to study, observe and learn what they do. I’ve learned a lot from my teachers and those I’ve played music with. I feel very blessed in that regard.

I remember one time I was taking a lesson from an orchestration teacher. I was trying to learn how to write things for orchestra and creating arrangements. I was talking to him about counterpoint and about creating melody and harmony. He was using a No. 1 Pencil. And I never thought to use it before. But it set me free. A No. 1 Pencil writes darker, so in clubs where the lighting isn’t so great, you can see what you’ve written down better. And it also erases better. It was a silly thing, but it ended up being so important.

I’ve learned so much just from even observing how people tune or take their guitar out of the case, how they sit. There’s a lot to it. You learn a lot from hanging around other people and observing them. Language is often limited. There is all kinds of stuff going on with music that cannot be communicated verbally. You can learn so much about vibe, posture and attitude just from watching really great players play. And if you can take lessons from people, you should do it. I still take lessons from people, because it’s so great to learn.

Everything is a learning experience. I think about the concept of a stand light: So many times, I’ve gone out and played a gig without one, and I realize halfway through I can’t see anything. Or even just something like using clothespins to prevent music from blowing away can totally change your experience.

Musician Coaching:

You posted a blog entry on your website about your experiences that people really responded to. What made you decide to write the article about being a musician? Were you getting asked about it a lot?

DB:

I really didn’t think anyone would ever look at it, because I feel like not many people know about my work.

The media goes through cycles where a politician will be part of a scandal. And all of a sudden, everyone is talking about it, even though it has nothing to do with them. And then there will be an ABC Afterschool Special-type thing about the topic, even though it has no real bearing on anyone’s life. For example, what Brad Pitt said to Angelina Jolie last week really has no meaning to me personally. But it will become a huge topic that is everywhere. Next week, it will be something else or someone else.

Musician Coaching:

When you wrote it, were you feeling that the DIY music business had become like Brangelina?

DB:

There were just a lot of people complaining about things. People were loving and reposting the articles on Facebook about how awful it is to be a musician, how difficult and screwed up everything is. But I wanted to write something that was encouraging. I just wanted to give a positive response. I wanted to acknowledge the reality, but then encourage people to build something. It doesn’t matter what we think about it or how we got here. The horse is going that way, so let’s turn around in the saddle and go that way.

I just saw this bumper sticker the other day that said, “Driver carries no cash. He’s a musician.” I’m not really impressed by that. There’s this whole idea going around about how it’s so difficult to be a musician. But the richest people I know are musicians. They are much richer than the stockbrokers, brain surgeons and lobbyists I know. That may be my own skewed perspective, because I’m in music. But so many times, reality is not in the metanarrative. When I wrote that piece, I wanted to present my own experience in a humble way. I didn’t really expect it to be received very well. A lot of times, if you have something to say that is not a sound bite, people label you as a kook. No one really cares if it’s not in the sound bite.

The sound bite is, “It’s horrible being a musician. Digital this, sales are down that, it all sucks.” You read that over and over again. And you have to ask yourself if it’s real. My friends are in music and making awesome records, putting their kids through college. I don’t get it. I just wanted to make a positive statement and give struggling musicians some suggestions based on my own experience and the experiences of people around me about things they can try that will stop them from getting bogged down. I’m so far down that the underground seems commercial to me, so I really didn’t think anyone would pay attention. I was trying to be honest and uplifting and provide information, and it felt great that a lot of artists – and not even just those in music – read what I wrote and got some benefit out of it.

To learn more about Danny Barnes and his music, visit his official website. You can also check out his widely-read, optimistic piece about making a living playing as a musician here.