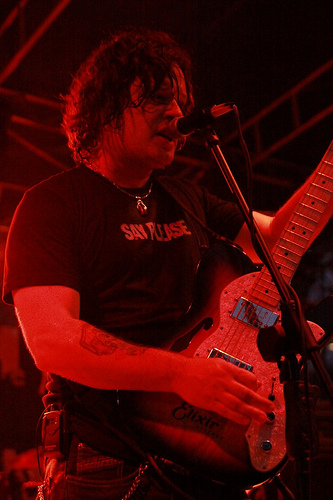

Music, Radio and Touring with John Wozniak Pt. 1

This is a re-post of Part 1 of a two-part interview from late 2009. Be sure to also check out Part 2.

John Wozniak has worn many hats during his fifteen years in the music industry: Singer/Songwriter; Record Producer; Owner of Mushroom Studios (Vancouver, BC) and A&R Rep (Capitol/EMI). But he’s probably best known as the creative force behind Marcy Playground, the band that brought you the 1997 hit “Sex and Candy.” Almost 12 years later, John continues to write and release albums with the band, and I was able to catch up with him by phone last week, as Marcy Playground’s “Leaving Wonderland 2009/10” tour found their bus rolling into Houston Texas.

John talks about the experience of writing a hit song, recording and getting signed to a major label. He also shares his thoughts on how the industry — and in particular radio — has changed for artists since the 1990s.

Musician Coaching:

You’re one of those artists who was playing locally and then wrote a big fat hit song and had national exposure.

JW:

That’s the really short version. The longer story is that, in 1995, the Executive V.P. of A&R at EMI Records in New York, a man named Don Rubin, listened to a copy of a solo album I recorded in 1990 called Zog Bogbean: From The Marcy Playground.

Musician Coaching:

Zogbog… what?

JW:

[laughs] Zog Bogbean. It was the name of a character from some short stories I wrote as a kid. – Anyway, he gave a few stacks of CDs, that included my album, to his summer intern while she was working for him and before she left in September, he asked her if there was anything he’d missed that she liked. She said she’d been listening to Zog Bogbean all summer and really loved it. So Don checked it out, and eventually got in touch with me out in Olympia Washington, where I was going to college. After a few conversations about what my plans and aspirations were, I remember him saying to me, flat out, “I absolutely love your music, John. But being all the way out there, you’re in kind of an impossible place for us to work with you right now. If you lived in New York, it would be a completely different story.”

Olympia had two labels at the time, both indie icons: ‘Kill Rock Stars (KRS)’ and ‘K Records.’ Kill Rock Stars was all Riot Grrrl music, and K Records was too “indie cool” to be interested in my music. So, shortly after my initial conversations with Don, I made the decision to drop out of college and move to New York. And that decision changed my life.

When I got to New York I didn’t call Don immediately. I wanted to get all my ducks in a row first, and record some of my newer songs. I wanted to hand him a great sounding demo, which I think is one of the keys when you’re starting out.

As much as people call this business of ours “The Music Industry,” it’s actually more accurately called “The Recording Industry.” You really have to have a kick-ass sounding recording in order to get people’s attention in this business. Labels know that your demo wasn’t recorded by Butch Vig or Jack Joseph Puig, but if it sounds like it was… Okay, now you’ve got somebody’s attention! I mean, I saw you in your office, Rick, back when you were working at Elektra, with stacks of demos on your desk. I know how it works. There’s the “interest stack” which is a short stack of material you’ve already checked out, heard some cool stuff on, and want to give a second listen to. You also have the “priority stack”, which comes from solicited sources like managers, lawyers, associates at the label, and your boss. Then you have the, “Oh-my-God-I-can’t-believe-I-have-to-wade-through-this” stack of shit that comes in through the mail, totally unsolicited. That stack usually takes up a small storage closet somewhere in the building, right? Yeah, I know.

I did A&R at Capitol/EMI in Toronto for almost two years. I was in charge of listening to every demo that came in to the building. I was also put in charge of prioritizing which showcases our staff would attend during various music conferences. And, I don’t mind telling you, having that experience from the other side of the desk really opened my eyes. Given the volume of music that comes into a record label, it’s amazing that A&R people find anything to focus on. Deciding if it’s worth it to go to a club and see a band usually comes down to either… the strength of their demo, or a buzz on the band. Music conference like CMJ or SXSW, can be fruitful for labels, but exhausting to the ears. With hundreds of bands to see at SXSW, watching A&R people scurrying around, trying to manage their time, attempting to squeeze in certain artists and find out where the buzz is, becomes like watching a movie about a mad scavenger hunt from the silent-film era, where all the people have badges, checklists, and a cell phone. Most major label A&R people have absolutely no patience for “diamonds in the rough.” If you’re a great songwriter but can’t sing, play, or perform… then send your demo to a publishing company, not a major label. They don’t care. An indie label might care, if you’re as talented as someone like Daniel Johnston… but the majors don’t. Why?… because they don’t trade in great songwriters, they trade in good-looking performers who make cool-sounding recordings of marketable songs. That’s their business. They don’t actually care if your mom writes your songs, so long as they’re hits, and you look and sound cool playing them.

Musician Coaching:

How did you go about getting a great recording?

JW:

I got some musicians together and found a good recording studio on Long Island that we could go into for not much money and record a really great demo. We visited a few studios around New York but, in the end, I settled on Sabella Studios. They were the only one that actually had a hit record on the wall. It was Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back,” which, if you study your music history … you know how significant of an album that was. The owner, Jim Sabella, who is just a really wonderful human being, gave me a copy of their studio CD sampler to take home. Everything on that sampler sounded like music I would listen to. They had the most professional sound.

The other reason I liked that studio is because it’s actually in the basement of a house out in Roslyn. That’s not to say it’s a home-studio, ’cause it’s really not. It’s a commercial studio, it’s just small and intimate. The acoustics were designed in the early 80s by the guy who designed John Lennon’s studio. Jim has a vintage Neve console, tube mics, and an incredible collection of outboard equipment.

We spent a week in there and recorded ten songs live off the floor. I overdubbed some guitars and vocals, and we took the last two days to mix it all down. I was pretty happy with the results, and so the next step was to get in touch with Don Rubin again, let him know I was living in town, and send him the new demos. So that’s what I did. About a week or two after sending him the CD Don called me… and I could tell he was excited. He was like “John, we absolutely love this, we’re flipping out.” Apparently it took him that week to get back to me because he’d been waiting to play it for Davitt Sigerson (the president of the label at the time) and Brian Koppelman (the head of A&R).

Since we didn’t have any shows booked, the three of them asked if they could come over to the house where we rehearsed. At the time, I was on guitar; Jared Kotler… a somewhat-annoying friend of mine from high-school was playing drums, and our buddy Kurt Rosenwinkel was on bass. Some of your readers might know who Kurt Rosenwinkel is. These days, Kurt is considered by many to be one of the world’s most preeminent jazz guitar players and composers. His critically-acclaimed albums on Verve and Blue Note have led him to tour the world, headlining all the big jazz festivals. But 14 years ago, Kurt was just a good friend that Jared and I had from Philly, who dug my music and enjoyed sitting in on bass from time to time. He also introduced me to the two people who would become Marcy Playground with me, bassist Dylan Keefe, and drummer Dan Rieser.

So, that night, when Don brought Davitt and Brian to see us, we only played five or six songs before they stopped us in order to talk. I remember at one point, after talking for a while, Davitt just folded his arms and said, “Alright so, I think we all agree… let’s make records.” And that was it.

EMI had a pretty dominant roster in the ’80’s with David Bowie, The J Geils Band, Kim Carnes, Corey Hart, Kate Bush, Billy Idol, Queensryche, Tina Turner, and Pet Shop Boys. But by 1995 Alternative and Grunge had basically knocked all of those artists off of the MTV playlist, and the label realized, probably too late, the value of developing new talent. So we got lucky, in the sense that, I was being scouted by Don during this very brief window of opportunity in the ’90’s, when EMI was actively signing unknown artists. Besides of us, their development roster included Fun Lovin’ Criminals, Five for Fighting, Patti Rothberg, Little John, and Jeffrey Gaines. Some went on to success, some didn’t.

Musician Coaching:

Did they change the record?

JW:

No, and I know that that’s very unusual. I asked Davitt about going back into the studio to re-record everything, and his response was something to the effect of, “Yeah, we just really feel like you guys have it here. We feel like this is the record, and it doesn’t really need anything else except for maybe a couple more to fill it up, since there’s only ten.” So that’s what EMI released, my demos from Sabella.

It took a while to choose a lawyer and have him negotiate the deal with EMI so, by the time I finally went back to Sabella to finish off the album, we had settled on “Marcy Playground” as the band-name, and I also finally had a real line-up, with Dylan Keefe on bass, and Dan Rieser on drums. The three of us spent a week at Sabella and finished the album off with a couple more songs. So, when all was said and done, our debut record, the one with “Sex and Candy” on it, took no more than two weeks to record and mix.

Actually, here’s a funny story about “Sex and Candy:” I’d written it in 1992 on a spring break home from college. It was now ’95-96, and I felt like it was a bit “over” for me. I’d been singing it for 3 or 4 years, and didn’t think it fit with the newer material on the record. At one point I was thinking about pulling it from the CD. Oh man, I remember Ken Gioia, who was our engineer at Sabella – and now works for Digidesign – heard me say that, and immediately jumped up and down, and said, “No way man, you’re nuts, that’s my favorite song!” He got pretty animated about it, so I figured I should probably leave it on. And, of course, it went on to be the monster that it was. So… thanks Kenny! Just goes to show, sometimes we’re not the best judge of our own material.

That’s how we got signed, the sub-context of which is that there’s no formula for how to get signed. And by the way, even if you’re lucky enough to get signed by a major, like we were, there’s still a lot of work you need to do before you can even begin to scratch the surface of success. Getting signed is the beginning of your journey, not the end. It’s like, “Welcome to Oz! You made it! Good for you! Here, take these keys, and that 15-passenger van, and hit those yellow bricks over there, and someday you might actually reach the Emerald City… but probably not. Have a nice day!” So that’s what we did for about a year. And then the unthinkable happened; EMI (UK) restructured their North American operations and closed EMI Records in New York in the summer of 1997. We were on tour in California, about to play a show in Sacramento, and we got a call from our manager that we had no label, no tour support, and no way to pay for gas home.

When they shut down the label we thought, “Okay, that’s it, we missed our shot. How will we ever pick up these pieces?” The only real success we’d had on EMI came from opening for Toad The Wet Sprocket on their “fan appreciation tour” in the Spring of ’97. We’d only had one radio station in Fargo add “Sex and Candy” into rotation. They loved the track, and so did their listeners. They were doing really well with it but, for whatever reason, the label was unable to convert that yardage into points – so that’s where we were. We were done for and stuck in Sacramento … or, that’s what we thought. Because, as luck would have it, about the same time EMI was closing, Chris Muckley, the music director at 91X in San Diego had begun spinning “Sex and Candy” on his show, and was getting a huge response from listeners that shocked even him. Within the first week it was Top Five Phones – top five most requested song at the station – and within two weeks it was the number-one-most-requested song on 91X. And this is a big station. 91X has a listening audience that goes all the way from San Diego to Los Angeles, reaching tens of millions of people. At the time Capitol Records (L.A.), and Virgin Records (NYC) were each deciding which EMI’s contracts they were going to pick up, which they had the option to do. In our case, due to the success 91X was having with “Sex and Candy,” that August in 1997, we were moved over to Capitol Records, where the machine went into total overdrive on our album. So, we kept touring, and picking up stations, and by the time the charts locked out in December for the holidays, “Sex and Candy” was the #1 song in the country on Billboard’s Modern Rock chart. And it stayed there at #1 for 15 consecutive weeks.

Musician Coaching:

Clearly that’s a story that’s for the most part from the bygone era. I can’t think of many songs for modern rock kind of bands that have done that. What has your experience been like subsequently, 12 years later? How have things changed?

JW:

Everything’s changed — dramatically. Let me address the bygone era aspect of it, because I couldn’t agree more. It’s never coming back. When you’re talking about broadcasting, you’re talking about an industry that suffered irreparable change at the hands of Bill Clinton, when he signed the Telecommunications Reform Act into law in 1996. That “reform” gave rise to companies like Clear Channel having the ability to come in and purchase virtually all of the nation’s large independent radio stations. The new law was supposed to create competition, instead it handed a near monopoly to Clear Channel. Prior to being taken over, stations could make a lot of choices on their own, but now their programming is tightly controlled by a corporate few. In some respects it’s been good, since Clear Channel has basically single-handedly wiped out something that has been a problem since the beginning of broadcast radio, which is the Mafioso-style control of radio programming by what are known as Indie Radio Promoters, or “Indies.” That’s a whole other story that I won’t go into right now. Suffice it to say, Clear Channel has gotten rid of a lot of the indie promotion people. Yet, in doing so, they have replaced the indie as the gatekeeper in getting your songs on radio.

I think that’s why AAA (Adult Album Alternative or “Triple A” Radio) has exploded over the last ten years. AAA stations are the stations that broke Dave Matthews, Ben Harper and Jack Johnson. It’s the only format in radio that is currently growing. They have more flexibility in what they play; because they’re independent. Some are commercial stations, but many are non-commercial “listener-supported” public radio stations.

So the bygone era for commercial radio is never really going to come back. But there is a new era dawning for AAA Radio that involves the collective power of SIRIUS-XM satellite radio, Internet streaming radio, small independently-owned commercial stations and, in particular, listener supported public radio. WXPN in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania is a great example of the power of public radio. I think XPN, at this point, is probably the largest AAA station in the country. They rival some of the largest Clear Channel stations, serving millions of listeners. If they decide to break a record, they can. It’s strictly up to them. So, you know, you can have a hit, it just might happen in a weird way. If you look at the history of AAA Radio, you’ll see a lot of hits that happened in weird ways. “1234” by Feist is an example. It didn’t happen at commercial radio; it happened because her video was featured in a TV Ad for the iPod nano, at which point Triple-A picked up the song and broke it to their audience of millions. All of a sudden Feist has a top 10 hit in the U.S. and is being booked on shows like David Letterman and Saturday Night Live.

Part 2 of my interview with John can be read here. You can also read more about John and his music on the Marcy Playground website.